The Octopus Garden: The struggle to reproduce

By Jim Barry, Senior scientist at MBARI

In 2018 scientists made a thrilling discovery off the coast of California. Two miles beneath the ocean surface, at the base of a deep-sea seamount they uncovered the largest known gathering of octopus in the world – 20,000 pearl octopus breeding in warm hydrothermal springs. Octopus were thought to be predominantly solitary, so this immediately led to the question - why are they breeding in such large numbers, and what is so special, if anything, about the thermal springs?

After its discovery, my lab group at MBARI and collaborators from the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary set about revealing the mysteries concerning this magical deep-sea octopus breeding ground.

Life is challenging for animals in the deep sea. The near-freezing temperature of abyssal waters slows the pace of life for most cold-blooded organisms, yet each must find a way to survive and reproduce to ensure the future of the next generation. We knew that the length of the brood period for octopus worldwide is closely related to water temperature - the eggs of octopus species living in warmer waters can hatch within days or weeks, while incubation for colder water species is much longer.

The longest known brood period was for the infamous “Octomom” a deep water species that brooded her eggs for around 4 and half years in 3°C waters. These pearl octopus however, live in waters near 1.6°C, where brooding would be expected to take as much as 10 years or more, a seemingly impossible task considering octopus mothers don’t feed whilst they tend their brood.

By measuring temperatures in and out of pearl octopus nests and monitoring the speed that embryos were developing, we were able to solve the mystery.

First, we found no nests where the temperature was low – they only select warm spots for their eggs. Second, we determined that the brood period is nearly 2 years, far less than the decade-long period expected for cold waters.

In fact, this brood period is nearly exactly what would be predicted from the average temperature (5.1°C) we measured in active nests.

While we don’t know for sure, it seems logical that the shorter brood period increases the chance that more eggs will hatch. We know that developing embryos are always at risk of injury, infection, predation, or other sources of mortality. For the very short brood periods of warm water octopuses, this may be unimportant, but for incubations lasting many years, these mortality risks are significant.

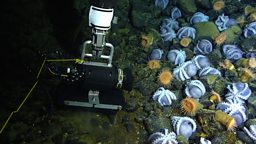

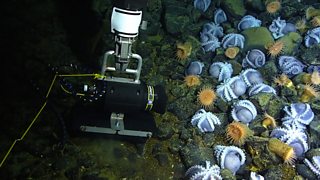

Working with the 91�ȱ�’s Planet Earth III team on this project brought its own benefits to our research. The need for close-up, high quality video pressed us to be more creative with cameras and lighting, leading to observations of pearl octopus that we would otherwise not have captured.

Intimate, close-up scenes of developing embryos made it easier to estimate how far along they were in their development, while we were able to witness the decline of the mothers toward the end their incubation in the tight shots we captured with the Planet Earth III team. Overall, working together has helped our insight into many aspects of pearl octopus biology and behaviour.

We now know that the warmth of the springs at the Octopus Garden give the embryos a better chance for hatching and early life, ensuring the continued success of the local pearl octopus populations.

Through it all, my perspective shifted from observing thousands of anonymous pearl octopus, to getting to know the lives of individual moms struggling to protect and hatch their brood as they approached the end of their own life.

Making Planet Earth III: Filming devoted, deep-sea mothers

The team film the world's largest gathering of octopus, 2 miles deep on the ocean floor.